Research

Even though speaking is learned at an early stage of development, it is far from a simple process. Rather, in order to speak even a single word, we must map the semantic concept we want to convey to a specific word, which must then be broken down into the minute phonological units found within our specific language system. My research fuses traditional cognitive psychology and computational methods from cognitive science to investigate how individuals navigate this intricate process.

Lexical Retrieval

You may recall instances in which a grandparent mistakenly referred to you by your sibling’s name, or perhaps worse, by the dog’s name. While it may be tempting to attribute this error to a lack of affection, it is in reality a reflection of the interconnectivity among related concepts and words. Bringing one concept to mind leads to the simultaneous activation of semantically related concepts, as well as the words we use to represent those concepts (e.g., Dell et al., 1997; Levelt et al., 1999). In addition, our recent experience and the surrounding context can also make related words particularly active in the mind. However, as we know, only one word can be spoken at any given time, such that having multiple related words in mind can actually result in production difficulty, or semantic interference. Researchers have used this phenomena to better understand the processes that govern lexical retrieval and selection. This line of work has been carried out in conjunction with my graduate advisor at Lehigh University, Dr. Pat O'Seaghdha.

How do we study it?

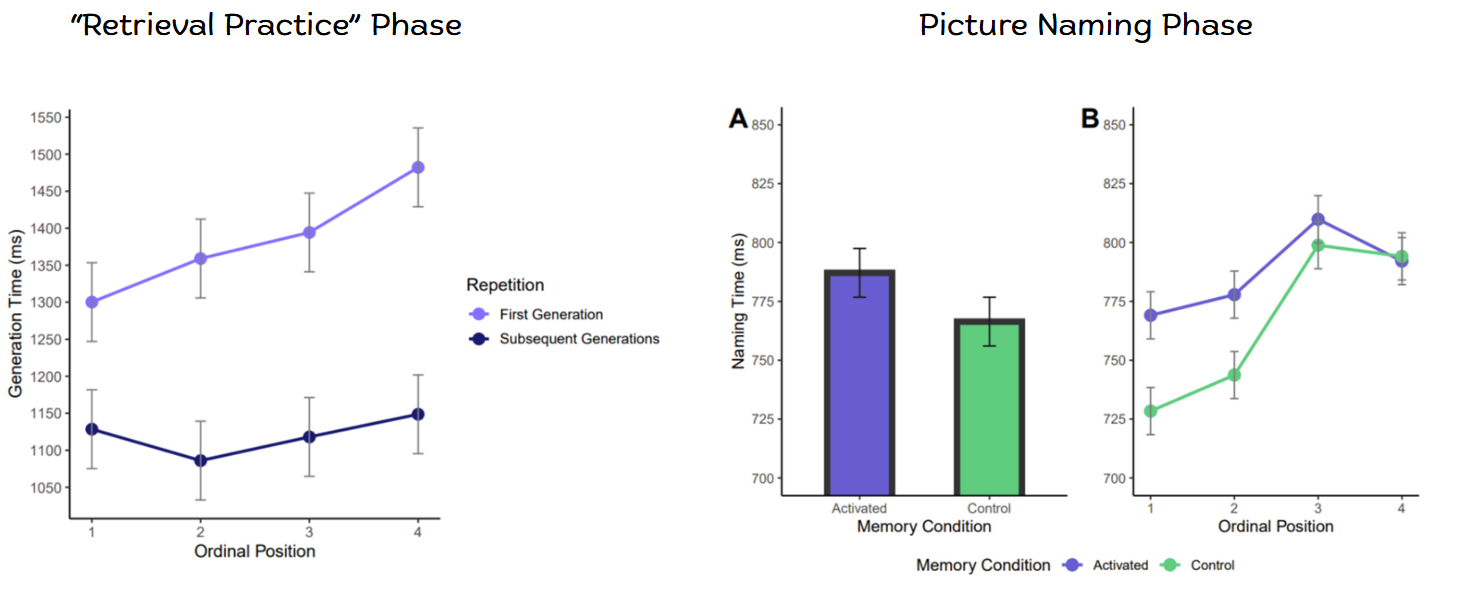

Semantic interference is often studied through timed picture naming tasks that require generation of names from memory. We typically measure how long it takes a participant to produce the name of the picture and make note of the types of errors they make. The general finding is that it takes longer to name a picture if you have recently named a related picture, and production difficulty increases linearly with the number of named associates. This phenomenom highlights how context and experience engage incremental learning mechanisms that directly shape our access to words. Check out this paper about a study we did comparing different naming paradigms, and what they can tell us about different types of semantic relatedness.

Bridging Language and Memory Approaches to Interference

This effect is markedly similar to the memory phenomenon of retrieval-induced forgetting (RIF). Even though they use very different methods, they find the same basic effect: recalling an item from memory makes it more difficult to recall semantically related items later on (Anderson et al., 1994). Researchers have posited that semantic interference in language production is essentially a form of retrieval-induced forgetting (Oppenheim et al., 2010; Navarrete et al., 2021), so in my dissertation work, I decided to finally test that claim. We designed an experiment that integrated the methodologies from language production and memory retrieval - we adopted the multi-phase design of the retrieval-induced forgetting paradigm, which entails an initial “practice” phase and a final retrieval phase, but used more sensitive language production measurements. We found that interference accrued linearly with the number of retrieved related items, directly mimicking the findings in the language production literature. In addition, we found that cued word retrieval during the practice phase made it more difficult to name pictures related to those words (“Activated” condition) later on, showing that the underlying mechanisms were not task specific. Together, these findings suggest that interference in conceptual-lexical retrieval should be studied in a unified framework. Check out this paper to read more about this study.

Computational Approaches to Lexical Search

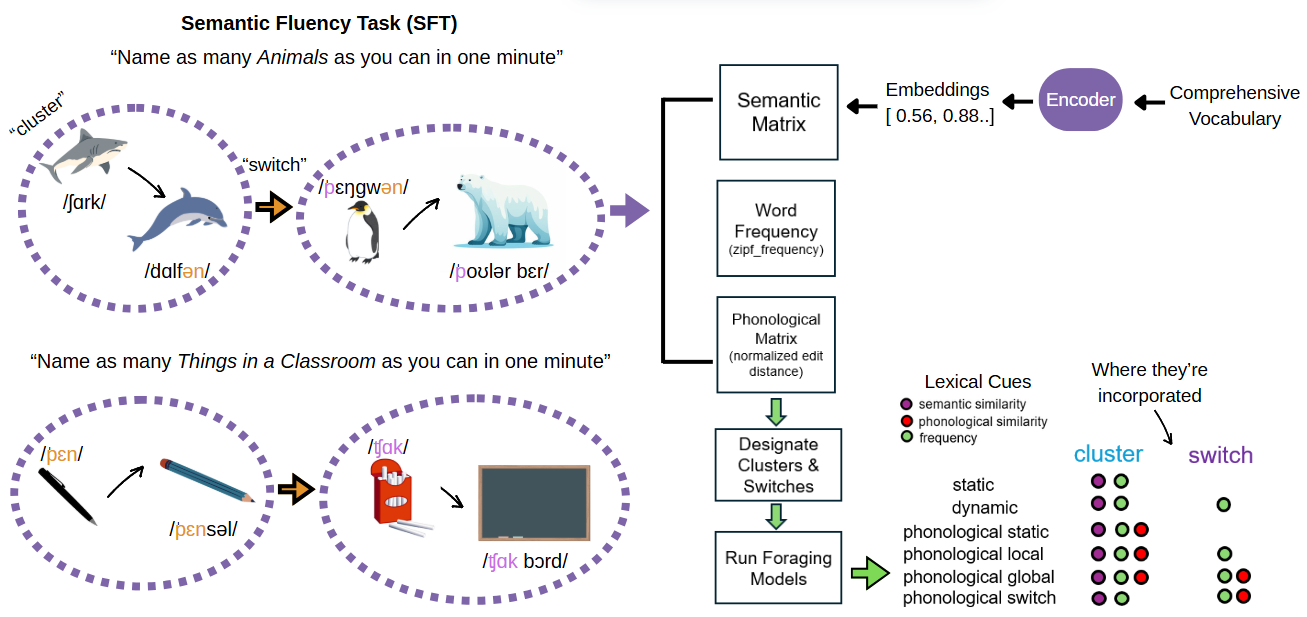

In my current postdoctoral position, I am working with my supervisor Dr. Abhilasha Kumar and our collaborator Dr. Mike Jones to investigate computational models of semantic search. Specifically, we are modeling the semantic fluency task to better understand the structure of semantic memory and how individuals search within it. In the semantic fluency task, participants are presented with a category (e.g., Animals) and asked to generate as many items as possible (e.g., shark, dolphin, penguin, polar bear). Researchers have found that people tend to retrieve words in related “clusters” (e.g., shark, and dolphin are both ocean-dwelling animals) and the way they “switch” to new areas of search mirrors the way animals optimally forage for resources in their environment (Hills et al., 2012). Even though the semantic fluency task doesn’t ask participants to consider how words sound, Kumar et al. (2022) found that people tend to use phonological similarity to guide their search within and across clusters (e.g., dolphin and penguin end in the same sound).

How do we model it?

Once we have a set of fluency lists, we first extract word meanings from distributional semantic models. We then use the Python package forager, developed by Kumar et al. (2024), to divide each list into clusters and switches and run optimal foraging models. Each of these models incorporates lexical cues, such as word frequency, semantic similarity, and phonological similarity, at different stages of the search process. We then examine how well each model predicted the data, taking into account differing model parameters.

Search in Different Types of Categories

Computational models of semantic search have typically been studied in taxonomic categories, such as Animals. However, as I learned from my training in language production, different types of categories are prevalent in cognition, and they influence lexical retrieval in different ways. These include thematic categories, where items are related by virtue of often appearing in the same context (e.g., Things at the Beach), and ad hoc relations, where relations serve the same external goal (e.g., Things to Rescue from a Burning Home). To invesigate semantic search in these different types of categories, we collected over 1200+ fluency lists from two taxonomic categories (Animals and Occupations), two thematic categories (Things at the Beach and Things in a Classroom), and two ad hoc categories (Things to Rescue from a Burning Building and Excuses for Being Late). We then examined the properties of items retrieved in these categories and ran fully nested optimal foraging models. We found that one size does not fit all for broad category types. Rather, the structure of each domain makes search unique, with some domains containing clusters of items with a shared word (e.g., Things in a Classroom) and some with a shared syntactic frame (e.g., Excuses for Being Late). However, model performance was poor for ad hoc categories, suggesting that current language models are limited in their ability to mimic the flexibility found in human cognition. Check out our Cog Sci Paper to learn more about this project.

In the Pipeline

We are in the process of extending this work to examine search in different clinical populations, including pre-lingually deaf individuals with cochlear implants and people with aphasia. Stay tuned!